In a sentence: A strong African woman casts off the

restraints of a slave’s religion, challenges whitey’s gods, and pushes through

to a way of life that is more natural, productive, and happy.

It doesn’t take long for nearly every intelligent author in

the course of their career to weigh in on the one topic most try to avoid until

they have had at least a small amount of success under their belt. The question

of religion and of God are nearly inevitable in an author’s career, and I enjoy

the challenge of searching/waiting for works which reveal authors’ best kept

biases and most petty/profound insights. Sometimes I am devastated by the

inanity and childishness of the reveal, and other times I am deeply moved and

persuaded that there is more to the author than her works generally exhibit.

Either way it’s entertaining.

So I was excited to stumble upon a work of George Bernard

Shaw that performed quite well on this front. Mr. Shaw has thrown his hat in

the ring of authors who have spoken out quite bluntly about God and religion,

and he pulled no punches. Not only did Shaw tangle with millennia of Christian

tradition—a.k.a. ‘God’—in the epilogue of the book, but he also slammed his

atheist brothers and sisters for presuming to banish transcendent ‘meaning’

groped for in a mythos, and castigated agnostics for not committing either way

and thinking to sidestep the question altogether (“mere agnosticism leads

nowhere”). This much was made explicit only in the essay at the end of the book

about the failure of modern Christianity, severed as it is from its original

context and embellished and contorted in order to fit two millennia of evolving

sensibilities and changing environments. But the beginning and middle of the

book didn’t make the final comments any easier for the faithful to swallow.

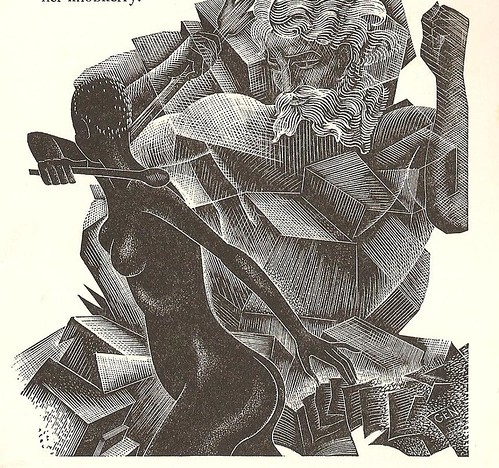

Shaw’s heroine, called ‘the Black Girl’ throughout, is a

smart, strong, African woman with as healthy a glow to her spirit as to her

earth-strong skin and body. She was, in Shaw’s words, “a fine creature, whose

satin skin and shining muscles made the white missionary folk seem like ashen

ghosts by contrast.” And with this social commentary on the rooted superiority

of African blood, body, and brain compared to the ‘ashen’ feebleness of their

western ‘saviors’, the author sets up a contest between his protagonist the Champion

of religion—namely, God. The Black Girl had been converted to Christianity by a

sad, single missionary woman who had found no satisfaction in her life, and the

Black Girl decides to go travelling through her jungle to see if she could find

the real God of the Bible that the missionary had depicted. She strides off

into the jungle, her knobkerrie in hand (a sort of club with a knob-tip used in

hunting and battle), naked and shameless as the earth who mothered her.

Throughout the story she meets with different versions of

the God of the Bible, each representing a successive stage of god-progression

from blood-thirsty Lord of Hosts, to the God of Job and Micah, to the ascetic

and passive Jesus who speaks of a kind of love that consumes individuals for

the sake of the collective and frees no one. She debates with each of these gods,

and ultimately moves on in search of a more perfect deity that offers more

answers.

Perhaps the most interesting part of the story is when the Black

Girl discusses God with a few enlightened westerners, and is told by one of the

more honest ones that it were best that the Africans—who were “stronger,

cleaner, and more intelligent”—not be taught to believe in the “simple truth

that the universe has occurred through Natural Selection, and that God is a

fable.” Why would this behoove the Westerners to teach? In the words of one

pale-thing, “It would throw them back on the doctrine of the survival of the

fittest…and it is not clear that we are the fittest to survive in competition

with them...I should really prefer to teach them to believe in a god who would

give us a chance against them if they started a crusade against European

atheism.”

And there Shaw has put it about as succinctly and potently

as he could. The Black Girl has felt the bottom of Christendom, and is ready to

break out of the religious labyrinth that had been designed for the Third World

by Western imperialists (though I don’t believe that the suppression of Third

World freedom by Western religious controls is necessarily a conscious thing in

all cases, but I wonder if white faithful folk would change their tune if they

weren’t the saviors, and felt more in need of the saving). The Black Girl finds

no theology which could deliver to her the perfected essence of the imperfect,

traditional, Christian God with its heterogeneous limbs, faces, and purposes.

The God she seeks doesn’t exist, and she ends up marrying a good Irishman who

believes that “God can search for me if he wants me” (not bad terms to be on

with God, if God is good that is). She later becomes a mother, reflects on the

futility of wasting her life making assumptions about God and chasing mirages,

and in the distraction of living her life and taking care of her family and

children, completely loses interest in the search for a God whose absence didn’t

ultimately affect her much. Later, after she had raised her children, she

considers again taking up the search. But “by that time her strengthened mind

had taken her far beyond the stage at which there is any fun in smashing idols

with knobkerries.”

A brilliant little ending for a brilliant little book about

the triumph of humanity over a few of its stubborn and isolated beliefs. It’s

not that Shaw had no appreciation for Christianity—“at worst the Bible gives a

child a better start in life than the gutter”—but he urged his fellow Sapiens

to put behind them the cruder elements of a faith that must be outgrown, and

make progress in the search for what William James called, “the More, and our

union with it.” He knew the danger of a closed mind, and when one or more

people are not willing to move forward and question tradition, things like

Christian religion and the Bible become a little more than an impediment to growth—“[if]

we cannot get rid of the Bible, it will get rid of us.”

Now all I need is to find me a knobkerrie and crack some

ignorant skulls with it. And…I have learned nothing.