Tuesday, January 14, 2014

Review of Shakespeare's Star Wars

Bustin’ a stitch doth make the hours seem short. I asked for this book for Christmas for shins and grins, and it didn’t disappoint…too much. The Shakespearean soliloquys, true to form, drew out new flavors in complex character development. It was fun to have someone like Doescher, who is invested in the Star Wars saga on a personal level and also well-acquainted with the expert storytelling of Shakespeare, retell a classic tale in a style which brings to light things I never caught the first time when watching the films. But mostly, it was just funny.

Some lines which almost madeth me to lose my continence:

[Luke] “But unto Tosche Station would I go, and there obtain some pow’r converters. Fie!”

[OBI-WAN] “…these are not the droids for which thou search’st.”

[Luke insulting the Millennium Falcon] “What folly-fallen ship is this? What rough-hewn wayward scut is here?”

[C-3PO to Han when Han explained a Wookie’s temper] “Thy meaning, Sir, doth prick my circuit board. ‘Tis best to play the fool, and not the sage…[to R2] pray let the Wookie win.”

[Leia to Luke upon first seeing him in a Stormtrooper’s armor] “Does Empire shrink for want of taller troops?”

[Han getting fed up with Leia’s complaints—can you blame him?] “Mayhap thy Highness would prefer her cell?”

And Doescher made a nice display of ‘the music in himself’ by incorporating well-known lines from Grandpa Bard himself:

[Beginning of the first scene, the rebel ship is being attacked, C-3PO is talking] “Now is the summer of our happiness, made winter by this sudden, fierce attack!”

[Luke asking about the blinking lights on the Falcon’s dashboard, which signified the loss of their deflector shield] “What light through yonder flashing sensor breaks?"

[Luke, encouraging other X-Wing pilots on their final attack on the Death Star] “Once more unto the trench, dear friends, once more!”

I loved how R2-D2 played a very prominent role as a secret conspirator and possibly the real lynchpin to the whole narrative, saving everyone’s skin, especially his petty and berating friend, C-3PO, on more than one occasion. He was able to speak intelligibly in soliloquy when aside, but in front of others he spoke only in beeps and boops.

“Around both humans and the droids I must be seen to make such errant beeps and squeaks, that they shall think me simple. Truly, though, although with sounds oblique I speak to them, I clearly see how I shall play my part, and how a vast rebellion shall succeed by wit and wisdom of a simple droid.”

Ah, R2. A doormat to some thou seemedst, yea, a small square of toilet tissue even, through which one’s fingers’ doth break. But Shakespeare spoke of thee truly: "This fellow is wise enough to play the fool."

Some parts of the book almost startled me by their profundity:

[OBI-WAN is speaking aside to himself about Luke] What shall I of the father tell the child? If gentle Luke knew all that’s known to me I’ll warrant he’d not understand the rhyme and reason for my words. And yet, what is’t to lie? To tell the truth, all else be damned? Or else to tell, perhaps, a greater truth?”

After this part in particular, it dawned upon me how many people misled (lied) to Luke about his or their identity, even if for a short time. His uncle, OBI-WAN, Yoda, Darth Vader…yeah, all the people that mattered. But OBI-WAN in his soliloquy believes that the full weight of the truth wouldn’t have been accepted or recognized immediately by Luke even if he had heard it. Then again, maybe OBI-WAN was just being a drama queen. He did, after all, do things like pretend to look and sound like a monster to scare away the sand people instead of just confusing them with a Jedi mind trick, told the guy threatening Luke that Luke was a “little one” and wasn’t even “worth the effort”, tried to negotiate cooly with Han Solo, but ended up congratulating himself on offering Han 7,000 (of Leia’s money) more than Han asked for, called Darth Vader “Darth”, as if ‘Darth’ was a first name and not a title, and allowed himself to be chopped in half by Vader as if he was surrendering when it was very clear that Vader was winning anyway. So, yeah, maybe he was a little bit of a drama queen. Now, where was I?

The most hilarious scene is where two Stormtroopers are debating back-and-forth about whether or not there were still people aboard the Millennium Falcon after it had been brought into the Death Star and inspected. One Stormtrooper convinces the other that his worry is just an over-active imagination.

Guard 1: Thou art a friend, as I have e’er maintain’d, and thou hast spoken truth and calm’d me quite. The rebels hide herein! What vain conceit! That e’er they should the Death Star enter—ha!

Guard 2: It warms my heart to see thee so restor’d, and back to thine own merry, native self.

Han: [within] Pray, may we have thy good assistance here?

Guard 1: [to Guard 2] So, let us go together, friend. Good cheer! [Guards 1 and 2 enter the ship and are killed.]

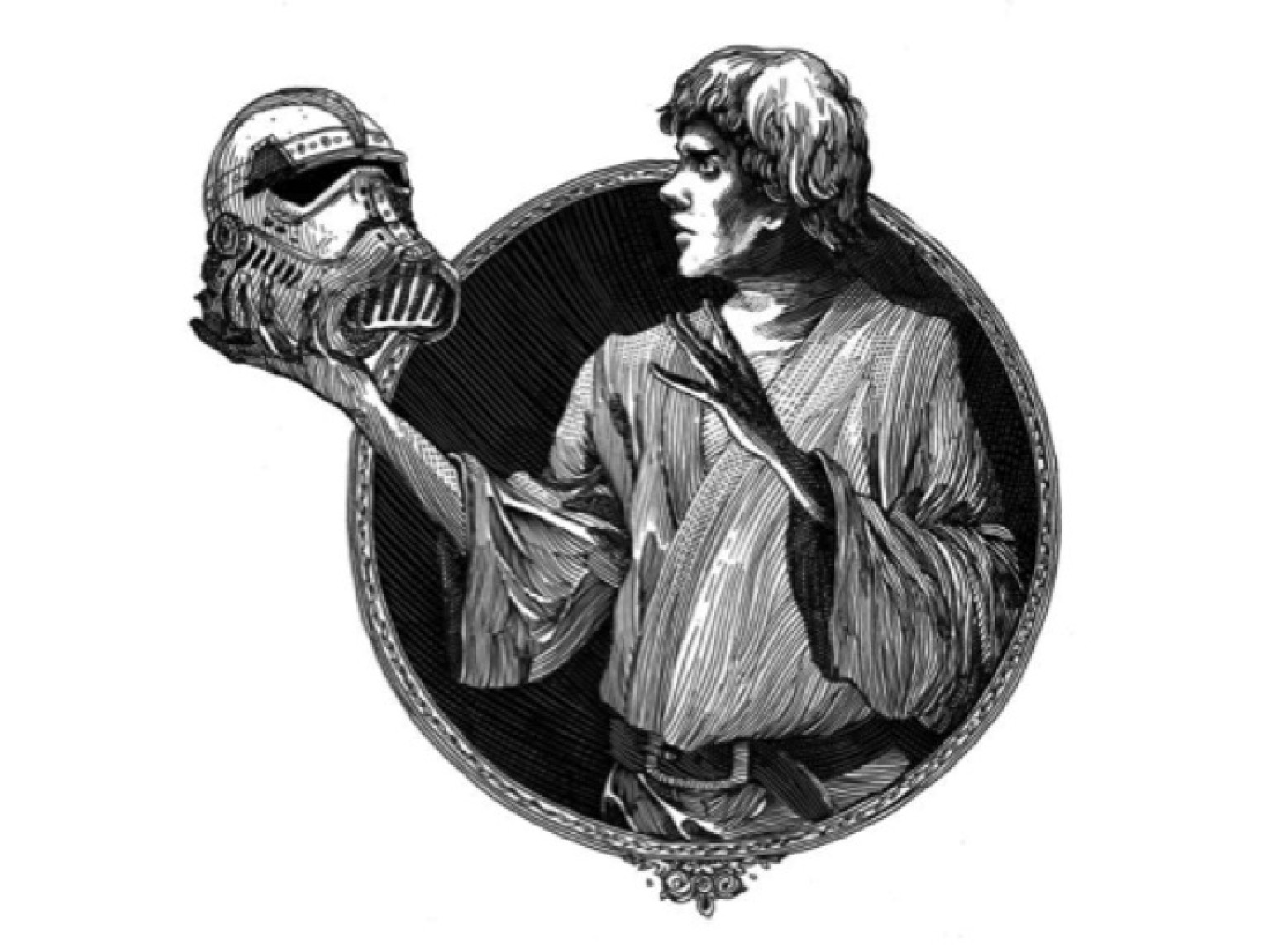

Yet, as with many other books, what began so well, ended too soon. The first half was extremely amusing, and there were some moments that kept it interesting throughout (e.g. Luke’s soliloquy to the mask of a Stormtrooper whom he killed for the uniform), but it started to drag. Maybe it took itself too seriously? The author never strayed from iambic pentameter, and though that is indeed a feat, it’s a rather uninteresting one to me, and limited Doescher’s options. Or maybe, I’m thinking, he knew that this book was only going to be interesting as a novelty, and never in his wildest dream expected anyone as big a nerd as me to read it from beginning to end but only read excerpts out-loud to guffawing friends.

Well, I love Shakespeare, and I love Star Wars, so the idea as a whole was a good fit for me. Not sure I’ll read the next book if it comes out, but I may change my mind. Maybe the novelty hasn’t completely worn off. But for now, parting is more sweet than sorrow.

Sunday, January 12, 2014

Review of Slaughterhouse Five

No doubt about it, Vonnegut is an extremely talented writer who

knows how to bolt a reader’s butt to the seat. He’s intelligent enough to know

that other intelligent people don’t want the same old thing written in the same

old way. In Slaughterhouse Five our boy Kurt keeps things fresh and moving the

whole way. It is a spellbinding display of creativity, facetiousness,

profundity, and meta-storytelling. He plays with writing the way the Globetrotters

(are they still around?) play basketball: he makes a circus out of the things

that other people take WAY too seriously. Why does he do this? Because he can.

This guy may never have followed with gusto the ‘Robert’s Rules Of Order:

Writer’s Edition’, partly because he sees that rules are, from the very

beginning, all just a big joke. Then again, he doesn’t give the impression that

he doesn’t understand the rules, but rather that he has out-grown them. It’s as

if he had played within the archaisms of traditionally structured fiction/non-fiction

for far too long, and was ready to create something new.

His characters are unpredictable

and the plot is sci-fi mixed with some of his own biography. Vonnegut was

writing loosely about his experiences in WWII prison camps and about the fire-bombing

of Dresden (which killed more people than the atomic bombing of Nagasaki and

Hiroshima put together), but he was also writing what he felt and thought, as

if his haphazard thoughts were actual events (beyond stream-of-thought), contorting

characters into hysterics that made you want to weep in one paragraph, and

laugh in the next. Sometimes, he included bland factual information,

definitions even, to make it all feel as authentic and pointless as life itself

sometimes is experienced. In this aspect his genius is especially showcased. He

understood that stories are artificial re-structuring of events that were

initially manifested as meaningless or inhumane accidents—inhumane in the sense

that human beings are not announced in the mundane as the center of the mystery

of life, and may not even be a clue to life’s meaning. Histories and

‘nonfiction’ are posthumous renderings of happenings that had no storyteller

there to say how to process it for food or hope, and they recreate an angle

from which to view events as if there were spectators and stadium seating all

along. At the beginning of the book he writes:

“It is so short

and jumbled and jangled, Sam, because there is nothing intelligent to say about

a massacre. Everybody is supposed to be dead, to never say anything or want

anything ever again. Everything is supposed to be very quiet after a massacre,

and it always is, except for the birds.”

Fear, suffering, and death do not have narrators, only

stories do. And stories are not lived,

they are told after they are all dead

and gone (a la Sartre). Vonnegut senses this disjunction between what we live

and what we tell, and attempts to imitate the feelings of live living in a disjointed, discursive, personal-impersonal style

that is fun and engaging.

The whole idea of time-travel and aliens (Tralfamadorians)

frees the author up to pull just about any literary stunt legally. It’s his way of saying, “Let me tell the story how I want

to tell it. If it helps, just pretend the protagonist could time travel and was

abducted by aliens at some point.” I love how the Tralfamadorians were so

entertained by human perspective. They helped Billy understand how precious

life was—how precious his life

was—even to the extent of upending his idea of body-image.

“Most Tralfamadorians had no way of

knowing Billy’s body and face were not beautiful. They supposed that he was a

splendid specimen. This had a pleasant effect on Billy, who began to enjoy his

body for the first time.”

They also explained to Billy that humanity’s provincial viewpoint

is like looking at a landscape through a long, narrow pipe

which is fastened to a train moving continually, never backing up, showing

people like Billy only part of the whole picture in a constantly shifting, miniature

window to the world. This is how Vonnegut probably conceives of time and the

limited scope of human understanding. Sounds about right to me. Though, if these aliens are metaphors for a broader perspective, Vonnegut's not doing a good job of following their advice, and I think for good reason. He writes, "there is nothing intelligent to say about a massacre," and later, "That's one thing Earthlings might learn to do, if they tried hard enough: Ignore the awful times, and concentrate on the good ones"; but apparently 'think nice thoughts' isn't as convincing practically as it sounds rhetorically. How do I know? Because Vonnegut wrote a book about the fire-bombing of Dresden. Microphone dropped.

I loved the ‘Vonuguttian’ spin on characters and events

throughout history, and especially his view of Jesus.

“So the people [first century

Jews/Rome] amused themselves one day by nailing [Jesus] to a cross and planting

the cross in the ground. There couldn’t possibly be any repercussions, the

lynchers thought. The reader would have to think that, too, since the new

Gospel hammered home again and again what a nobody Jesus was. And then, just

before the nobody died, the heavens opened up, and there was thunder and

lightning. The voice of God came crashing down. He told the people that he was

adopting the bum as his son, giving him the full powers and privileges of The

Son of the Creator of the Universe throughout all eternity. God said this: From

this moment on, He will punish horribly anybody who torments a bum who has no

connections!”

But, he also criticized Christians’ taking their story too

far and implying it is sad when people like

Jesus are tortured and killed, as if it’s not sad when it happens to normal people.

“The flaw in the Christ stories,

said the visitor from outer space, was that Christ, who didn’t look like much,

was actually the Son of the Most Powerful Being in the Universe. Readers

understood that, so, when they came to the crucifixion, they naturally thought,

and Rosewater read out loud again: Oh, boy—they sure picked the wrong guy to

lynch that time! And that thought had a brother: “There are right people to

lynch.” Who? People not well connected. So it goes.”

It became evident as I became more fully acquainted with

Vonnegut’s style that he has no clue about what the human race is supposed to

be or do. His anticlimactic tag after every reference to death, “And so it

goes”, which probably appeared some fifty times in the book, along with Billy’s

multiple responses of “Um” to awkward and inexplicable moments in life, was

hilarious, and are probably a rich commentary

on Vonnegut’s coping mechanisms. He’s more a critic than a leader, and maybe

that’s okay. He is a modern Socrates who does not have the answers, but who

dares to ask the questions. Of course, with these types, they have to be

careful not to suddenly slip into a ‘the-answer-is-obvious-you-stupid-bastard’

sort of tantrums that can characterize careless cynicism. Cynics have to

remember that they have chosen their path by committing to backing the

discussion up away from ‘easy answerism’ and fundamentalist moralizing towards

a ‘there-are-no-answers’ or ‘the-answers-aren’t-so-simple’ modus operandi. It

irks me when they suddenly switch methods because they are frustrated they

can’t say anything in the absolute, and it can quickly devolve into

name-calling. Unfortunately I see it happening in this book with the characters,

sometimes stumbling from scene to scene as Fortune’s flute, announcing their

utter lack of power and responsibility against the forces of nature, and at

other times griping about the treatment of some person or some leader that is hurtful,

as if there is such a thing as an ‘ought’ or choice people have in the matter. He

swings from recounting, I’m assuming with disapproval, the horrors of humans

inflicting pain on each other, and criticizing American capitalism with biting

words (“Like so many Americans, she was trying to construct a life that made

sense from things she found in gift shops”); to

stoic and even nihilistic statements like ““It was all right,” said Billy.

“Everything is all right, and everybody has to do exactly what he does,”” and,

“There are almost no characters in this story, and almost no dramatic

confrontations, because most of the people in it are so sick and so much the

listless playthings of enormous forces.”

So which is it Vonnegut? ‘Dem ivory towers look awful pretty,

but you can’t pick and choose when you want to fight and when you want to hang

back in the safety of passivism. That’s

called a hit-and-run. The copout of intermittent skepticism, mixed generously

with sudden outbreaks of moral superiority, can make a reader motion sick. However,

as obnoxious as I personally found this wavering, and as conflicted as I was

about how seriously to take his message, by the end of the book I felt that

Vonnegut had done a swell thing in writing it, perhaps in spite of himself.

He’s a dying man watching dying men, telling them this is the way it has to be,

but everything is going to be alright. On one hand, I’d rather not see people

give up so easily; but on the other hand, he didn’t have to call out

encouragement, however cloaked in passivism and resignation, to his brothers

and sisters. I think, in the end, he’s one of the good guys. And a great

writer. And if it is a moral train-wreck, it was fun to watch.

Friday, January 10, 2014

Review of Heart Of Darkness

Heart Of Darkness didn’t live up to the hype for me. I got

far more out of a study of the themes, background, and historical significance

than I did out of an enjoyment on the first read. There were quite a few

outstanding lines, but the narrative is maudlin and slow. I’m sure it was very

progressive for its time in provocative content and style, especially for tying

in psychological observation and analysis, and I’m sure that’s why even its form,

which now has been repeated and surpassed, is so appreciated by many to this

day. It is one of those books which I believe now belongs, stylistically at

least, to early 20th century literature, although the message is

still going strong.

In it, Conrad called out European colonialism, narcissism,

and conventional morality for what it was: an arrogant illusion of sanity and

progress. Heart Of Darkness was a

mordant accusation against western modernism which pretended to be able to tame

what is wild in humanity and what is unknown in the universe. It shows how

flimsy is our pretense of appearing to be in control and in ‘the know’. We

aren’t. We will always be far from understanding the universe if only by virtue

of the fact that we are ‘in’ it, and cannot distance ourselves far enough from

it and ourselves to achieve complete comprehension of our situation. We are thralls

to mystery and the eternal unknown within which we lie buried, and which will

forever expand itself through the cosmic wormhole running straight through the

center of our being.

Conrad uses this novella as a set-up for exploring the dark

and cognitively unassimilated parts of our psyche and existence, and this is

what he calls the “Fascination Of the Abomination.”

“The utter savagery had closed

round him—all that mysterious life of the wilderness that stirs in the forest

in the jungles, in the hearts of wild men. There’s no initiation either into

such mysteries. He has to live in the midst of the incomprehensible, which is

also detestable. And it has a fascination, too, that goes to work upon him. The

fascination of the abomination…”

What we can’t understand, what we can’t fathom, fascinates

us, draws us; and yet it is deep within us the inescapable and uncharted

territories of the human soul and unconscious mind. The civilized person

recoils at the thought of the natural world as an untamed force, but Conrad takes

us far inland, into the jungle, where large-framed pictures can’t hide the

holes, and aerosol disinfectants can’t mask the rank, bacterial growth of the

inhumane, intractable, and inscrutable features of Nature.

What can save one from despair in the face of this abominable

incomprehension? Conrad mocks the pseudo-answers of habits and custom. “Mind,

none of us would feel exactly like this [lost]. What saves us is efficiency—the

devotion to efficiency.” This idea of custom as the salve to our angst is

echoed later in the play by Beckett, Waiting

For Godot, who wrote that “habit is a great deadener” which stifles thoughts

and questions about life’s meaning which cause us distress. The great unknowns

of 1) foreign minds and powers in the universe that threaten to cause one harm,

and 2) the post-modern search for the purpose and meaning of life, may appear

like two different things, but each one causes a certain amount of anxiety,

and both are responded to by developing

methods and customs that help us feel like we belong and have a handle on

things. An interesting moment in the narrative comes when Marlow comes across a

book in a shelter in the dark, usurping jungle which was written on the banal

subject of nautical methods; and finds that the “singleness of intention” and

“honest concern for the right way of going to work” makes him “forget the

jungle and the pilgrims in a delicious sensation of having come upon something

unmistakably real.”

The whole point of this story is for the sailor in Conrad to

pistol-whip his safe, landlubber-readers with the question: how thin is the so-called

‘veneer of civilization’? He exposes culture as a thin coating which peels in

the heat of privation and conflict, and quickly flakes away leaving only the

real, bitter, and irreducible ‘hungers’ of the carnal instincts. “No [moral] fear

can stand up to hunger, no patience can wear it out, disgust simply does not

exist where hunger is; and as to superstition, beliefs, and what you may call

principles, they are less than chaff in a breeze…It’s really easier to face

bereavement, dishonor, and the perdition of one’s soul—than this kind of

prolonged hunger. Sad, but true.” His infrared scope identifies the vital

organs for the kill when he refers to modern man as “stepping delicately

between the butcher [food] and the policeman [safety].” Shot through the heart,

and Conrad’s to blame!!

There certainly appears to be some Victorian misogyny and

probably some racism infecting the fin de

siècle psychical baggage Conrad carries with him, but I do agree with Joyce

Carol Oates who wrote in the introduction that he was much more advanced than

others in is era, and did much to bring to consciousness the shortcomings of European

imperialism and bias. Specifically he challenged the moral-spiritual squalor of

Victorian decorum and opulence, and the tendency of Europeans to believe that

they were morally superior to the rest of the less developed parts of the world

by right of privileged birth and by dubious evidence of material success.

Conrad was intrigued with the contrast between the

bewitchment of the untamed wild (the “fascination of abomination,” and the

“horror” of Mr. Kurtz), and the cavalier complaisance of domesticated and

dissociated society (European greed, and the melodrama of Mr. Kurtz’s fiancée).

As an author he may have been experimenting with the idea of how to get back to

the raw primordial forces of nature and the unconscious without sacrificing the

discipline and stability of reason and community. The Wild is not as safe as it

is powerful. “I wondered whether the stillness on the face of the immensity [the

dark jungle] looking at us two were meant as an appeal or as a menace… Could we

handle that dumb thing, or would it handle us?” And in the end, Marlow returns

to his society, to his people and his customs and his habits. As if nothing

ever happened. But the spectacle of his

conscious duplicity is made very explicit in his final conversation with Kurtz’

fiancée-widow which caricatures the European attitude so wonderfully and magnifies

Conrad’s disgust for upper-class theatrics and hypocrisy. A year after Kurtz’s

death his engaged is still melodramatically woeful about her loss. She

practically swoons all over the place in front of Marlow boasting of Kurtz’s fine

modern ideals and righteous superiority, and begs of Marlow to corroborate her

convictions about her husband’s worth. Marlow

watches her histrionics and finally decides to play to them. Instead of

revealing to her that he saw the transmogrification of Kurtz and had witnessed

his final words in which he acknowledged the deep and writhing darkness that is

life—“Horror! Horror!”—he instead dumbs down the climactic ending of Kurtz and

tells instead that he died whispering her name to the very end. Isn’t that

nice. But he’s shocked and obviously disappointed that the ceiling doesn’t cave

in on him, or more importantly, on anyone else for lying the civilized lie of

hypocrisy and egocentrism. “The heavens do not fall for such a trifle.”

Did Conrad desire a peeling away of civilization’s mask, and

a return to the freedom, mystery, and power of the wild in some sense? Yes and

no. I think he saw in it, as did many modern psychologists and philosophers, a

raw, unharnessed force that could potentially help to enhance creativity and

vigor; or it could be very destructive. Mr. Kurtz went feral, to his own demise

and to the demise of others around him, but he successfully escaped the cheap

substitute of being a decent citizen

which couldn’t quite satisfy the primal instinct for adventure, mystery, and

power. Then again, he killed and died. So, there’s that. Tipping the scale

either way brings extreme ennui, angst of meaninglessness, suffering, or death.

And for anyone who doesn’t know, anything Conrad can do,

London can do better, and with less words. Jack London wrote The Call Of the Wild and The Sea Wolf on this same topic, and his

authorial execution of the ‘return to the wild’ theme, which was his specialty, is much more muscular and sportive in

nearly all of his works. Conrad is much more wordy and formal in his narrative,

while London lets loose with a cunning, creativity, and pompous confidence that

makes his words cut to the quick and soar above careful writers like Conrad.

Search your feelings Luke. You know it’s true. Just my

humble opinion. But I’m right.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)